Join the Town of Franklin and MAPC for our first public forum on Monday, March 7 at 7PM! This will be a hybrid meeting that takes place in the Council Chambers at Town Hall (please note the change in location) and over Zoom. Click the link below to register and tell us if you plan to attend in person or remotely.

Register for the March 7 Forum

History of Zoning in Franklin |

|

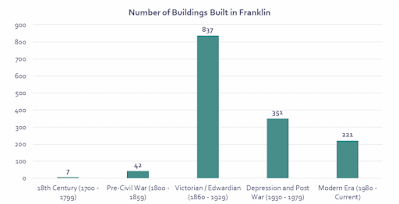

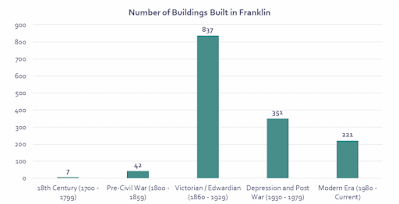

Franklin Center's building stock is largely historic, with two-thirds of the buildings having been built before WWII, and many much earlier. Franklin Center was predominantly developed around the turn of the 20th century, in the late Victorian/early Edwardian period from 1860 until the stock market crash in 1929. Close to 60% of all buildings in Franklin Center were built during this time, although some date back to the mid 18th century. |

|

|

| Source: MA Land Parcel Database, Franklin Assessor |

Zoning regulations throughout the United States, particularly in older communities, often result in conflicting goals between a zoning district's regulations and the existing development patterns of that area. Franklin's zoning code and associated districts were first adopted by the Town's Planning Board in 1930, after almost two-thirds of Franklin's current structures were built. As such, many of the most beloved buildings in Franklin Center could not be legally built today because of dimensional or use restrictions in the zoning regulations.

Prior to Franklin's zoning code being adopted, the primary modes of transportation for the average American would have been walking, bicycle, horseback, or using a streetcar transit system. In that year, there were roughly 217 cars per 1,000 people in the United States, a number that grew to 380 in 1955 and to around 800 in 2010. As family and individual car ownership continued to exponentially increase throughout the 20th century, so did a greater focus on zoning regulations to cater to the experience of motorists above all other modes of transportation. The below photo shows Franklin's Main Street back when its streetcar system was in operation

This meant that the physical form for urban, suburban, and rural communities was altered to fit the needs of car owners. Parking minimums for developments were established. Roads were built, widened, and then widened again to satisfy induced demand. As the world became more car-friendly, car ownership felt less optional and more obligatory. Jobs, schools, and places where people chose to spend their free time were further and further away from people's homes. Today, if a resident in Franklin or in countless communities across the country wants to get from their home to a place of business, they are most likely taking a car. |

|

Zoning's Impact on the Built Form |

|

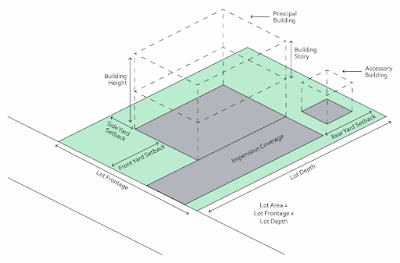

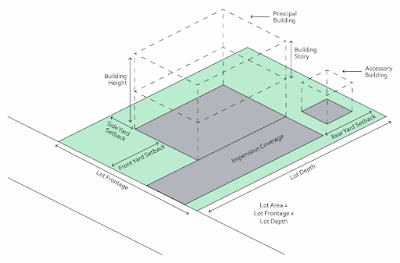

Impact of Dimensional Regulations The "look and feel" of a neighborhood depends on how a person traveling in the neighborhood is able to interact with their built environment. Zoning dimensional regulations dictate the size a buildable property can be, where building on that property can occur, and even the architectural design standards that dictate how those buildings must look. The diagram below shows the various dimensions that are regulated by Franklin's zoning code. |

|

|

| dimensions that are regulated by Franklin's zoning code |

Two of the zoning regulations which dictate the size of a property are lot area and lot frontage (see the Zoning Glossary below for definitions). They are both usually regulated as a minimum amount whereby a property owner would need to obtain a variance to build on a lot that has a smaller lot area or frontage than zoning regulations for that district allow. As we consider what this means for people traveling on foot or cycling, properties with a larger lot area are likely going to have more frontage, and as a result, it will take more time to walk past that lot.

Yards, also commonly known as setbacks, are a type of buffer that prevents a property owner from building anything too close to their front, rear, and side property lines and are also usually regulated as a minimum amount. Large front-yard setbacks can impede to access to a building by putting it farther away from the street. In commercial spaces, these setbacks are often reserved for parking lots. In residential spaces, it means larger front-yards. From the perspective of those who are interacting with their built environment, this means a longer walk across a parking lot to get to a store, or many long walks up and down driveways for trick-or-treaters come Halloween.

Building height and number of stories are dimensional standards that regulate how tall a building can be. Taller buildings with multiple stories can better maximize limited available land than a single-story building and are generally easier to obtain financing for from a bank.

On the other hand, buildings that are too high can also be unfriendly to pedestrians and cyclists, blocking natural light and creating a feeling of being lost in a "concrete jungle". The zoning code should strike a balance to allow for buildings to be built in a way that feels appropriate for someone who is interacting with them at street-level. |

|

| | Source: Downtown Great Barrington Cultural District |

A streetwall occurs when you have higher-density, multi-story development lining one (or both) sides of the street with little, if any, setbacks in the front and side. This creates a wall of buildings that offer storefronts with visual entertainment for pedestrians and awnings that provide shelter from harsh rain or sun. See the following photo from Great Barrington, MA for an example of a vibrant streetwall.The streetwall creates an urban form that encourages people to want to spend their free time there and transforms the sidewalk from a place of transportation to a venue for both daily adventures and special events (such as winter ice sculpture displays or a cookoff). Creating an environment where people will want to interact with the surroundings helps to create an area that feels vibrant and active and will also support the local businesses. |

|

Impact of Use Regulations Zoning use regulations explicitly dictate what can be built where. For example, a factory of a big-box store cannot be built in a residential district, something most would support. Such a use, with its odors, noises, and inherent dangers, could affect the quality of life for residents in a negative way. Zoning regulations help keep these land uses separate, often with buffers and space between them, ensuring that quality of life and the value of one's home is not negatively impacted by other land uses.

However, what we have learned in the one hundred years of enacting zoning regulations in the United States is that too much separation of land uses can have profoundly negative impacts on quality of life as well. As a society, we have used regulations to separate where we live from where we work, learn, and play, preventing the creation of vibrant neighborhoods and encouraging vehicle use. |

|

One of the things that we have learned is that a mix of uses in a downtown area, including residential, retail, office, and even light-industrial, helps to foster a wider variety of housing options and create a built-in customer base that will support local business. It is hard for downtown businesses anywhere to survive when there are no customers that live nearby. A mixture of uses combined with residents living near or above them helps to create downtown destinations, that in turn make a downtown more attractive to new businesses, shops, restaurants, and residents. The photo below is an example of a mixed-use development in Franklin with retail uses on the first floor and residential units on the floors above. |

|

| | Source: Franklin Downtown Partnership |

Impact of Regulations on Housing Costs Zoning regulations that unreasonably constrain what can be built on a site are directly tied to increases in housing costs. Setback regulations make the developable part of a property smaller than its area. Height limitations mean a person can only get so much usable space on their land since there is a literal ceiling as to how high a building can be built. Parking minimums mean valuable space is taken up that cannot be built on. All of these factors, combined with market forces related to supply and demand and personal preference on where people choose to live, inflate the cost of land and make development more expensive.

Fact finding missions to de-mystify zoning codes fall in the hands of developers, who must spend time and money working with architects, planners, engineers, and attorneys who can help determine what can be built where, and what the stipulations are for building in a certain place. The local municipality is a part of this, who must review submitted plans with accompanying permit fees that pay for the municipality's staff time. These processes can add hundreds of dollars to a small project, and thousands of dollars for larger projects, while adding time and uncertainty to the development process. The longer a project takes to get built, the less likely it is that the project will ever be built, a situation that no property owner or financing organization wants to be a part of. |

|

Accessory Building: Any building on a property that is reasonably related to the principal building on that property, such as a shed.

Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU): A self-contained apartment on the same lot as a single-family residence, either attached to or detached from the principal building.

Accessory Use: A secondary use of a property that is reasonably related to the principal use. A home-based business is an example of an accessory use.

Building Height: The vertical height (in feet) from the street-side of a building to the highest point of that building. The building or roof type may determine how the height is calculated, however, any part of the structure that does not enclose habitable space (such as a chimney, TV antenna, etc.) is not considered when determining building height.

Building Story: The portion of a building between the floor and either the roof or the floor above.

District: An area on a zoning map with uniform regulations which specify how the land can be uses and what dimensions a new building must conform to. All parcels in Franklin are currently assigned to one of 17 base zoning districts that serve residential, commercial, and industrial uses of varying densities.

Impervious Coverage: Anything covering the ground that surface water cannot penetrate, such as pavement.

Lot Area: The total area (in square feet) within the lot lines of a property, excluding any street right-of-way.

Lot Depth: The distance between the frontage line and the rear property line.

Lot Frontage: The portion of a property where the front entrance faces the street, measured along the street from one edge of the property to another.

Multifamily Building: A structure that contains three or more residential units, either for rent or condominium ownership.

Mixed-Use Building: A structure that contains a mix of principal uses. Generally, it refers to commercial use on the first story with residential units on the stories above.

Principal Use: What any property is primarily used for, such as residential, commercial, or industrial.

Rezone: The public process by which a zoning district for a property or collection of properties is changed, culminating in a vote by the Franklin Town Council.

Special Permit: A permit granted by a public board (usually the Planning Board) to allow for a use or increased density that is not guaranteed by right, but instead considered on a case-by-case basis. Variance: A granted exception from the use or dimensional regulations for a property by the Zoning Board of Appeals. Not all regulations can be granted exception. |

|

|

|